Who are you and how shall I know: On knowing my father and myself

It’s often said that the best teachers teach without explicitly teaching, whether by deliberately, or inadvertently through their own lives, holding up a mirror to our own and showing us how to be. To be taught is to be shown, or perhaps just to see, to learn how to engage with experience more than getting caught up in instruction or rules.

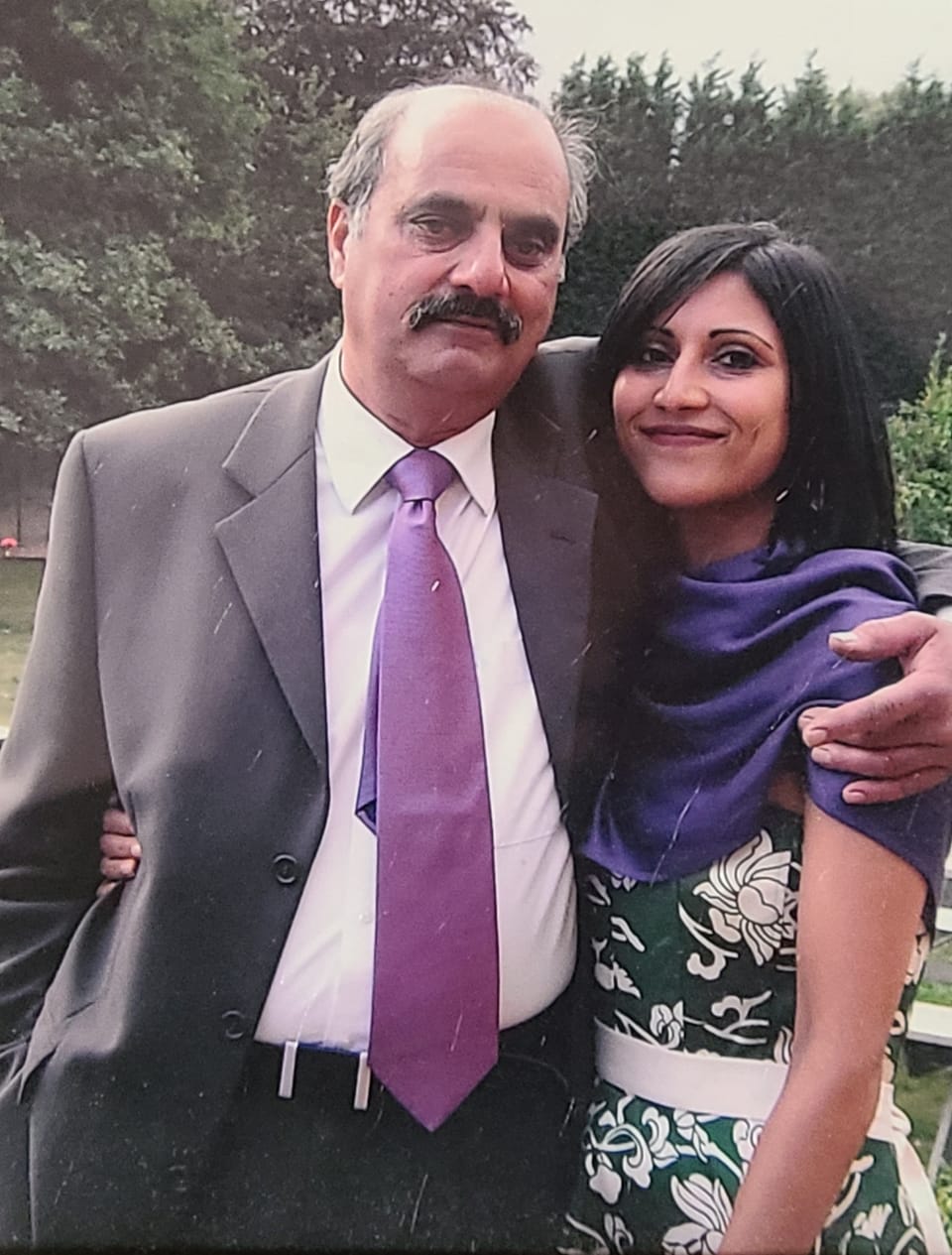

My father has always been a man of few words and yet he has taught me the most about facing life’s challenges with grace, care, courage and equanimity. Through showing me unconditional love (in spite of myself), and in the ways he has trod his own path in the true sense of a warrior - shaped as much by the invisible lines of lineage as by his experiences of strength and persistence in the face of struggle - he has shown me the importance of accepting both things and people for who and what they are.

The greatest gift I received this Christmas (not that I celebrate in any way but the time the holidays afford can itself be a gift) was spending time with my father in a rare dynamic that we’ve never really had, one that meant we could relax into conversation without the usual distractions.

He happened to be alone this Christmas, while my mother visited relatives in Pakistan, so he came to stay with me and my partner in the home we’ve now been making for a year thus far in the relative seclusion (or natural inclusion) of the countryside.

“This would have been my ideal life,” he told us as we sat around the dinner table, talking for many hours, absorbed as we were in hearing previously untold stories.

I’d intuited that this life I now live is in large part a belated realisation of a thwarted ancestral dream. My parents grew up in East Africa and had they not been robbed of the chance to choose and pursue their own dreams, they would have made a life surrounded by open skies and expansive lands, rather than the suburban estates of England’s East Midlands.

One of my fondest memories is of watching Little House on the Prairie and The Waltons with my father, or rather, seeing him enjoy the bucolic ideal presented on screen, an ideal that was once close to the life he lived growing up in Uganda. That is until the despotic agenda of the country’s then-newly appointed dictator Idi Amin determined that South Asians no longer belonged there.

But this is the story I’ve known, and I’ve told, one of his expulsion and survival, of bravery and thriving, his incredible and heartbreaking journey towards another kind of freedom, freedom in the sense of escaping violence. Whereas what I discovered in his own telling is that there is a whole other narrative, one of true liberation and a lust for life that is his true story, and now I appreciate more deeply, mine too.

“True words aren’t eloquent, and eloquent words aren’t true.” Lao Tzu

My father lives with a lot of unresolved trauma, a life interrupted. Not that he talks about it, as is often the way, especially with his generation and especially, for the most part, in the South Asian community.

I've tended to assume (because I will not pry or risk causing hurt to ask) that he prefers not to talk about the past because he doesn't wish to relive what he endured, what he witnessed and what he stopped himself from feeling when he had to get his father and the rest of his family out of Africa in sudden and life-threatening circumstances.

Yet there is so much more to it than that. "Why go there?" as he has often said, "the past is the past."

Readers old & new, it's good to have you here!

I hope you like what you find. The Most Important Thing is a reader-supported publication. If you want to be part of a growing, mutually stimulating space - which gives you access to the full archive, plus bonus content including monthly reflections, prompts and practice ideas for your own writing/contemplation, and an inspirational digest of readings and teachings - please consider a paid subscription.

SubscribeOn trauma and a narrative beyond the moral binary

Periodically over the years, I’ve asked him about his experiences, about the stories behind the sepia toned photos of his scouting days that are fading in the pages of albums, which were among the few belongings he and my mum were able to bring with them when they fled in 1971. Or about how his left eye was injured while he was a teenager and which he eventually had to have replaced with a glass replica when he came to the UK in what my mum ominously described as "a lot of pain". Or how he felt when his older brother made him work through the pain of his damaged sight (which he eventually lost in that one eye). Or about why he used to carry his father’s knife with him everywhere we went when we were kids.

His answers have always been short and I’ve always respected his privacy, to not “go there”. I’ve often wondered about and sought to guard against the commodification of trauma that can occur when tending to the stories of my family. Although these obviously have shaped my own, they are not in any way entirely mine.

Yet in seeking to reclaim and restore a narrative beyond the moral binary, and in the existential endeavour to know who I am via the routes of where and who I have come from, I have made my claim so as to understand, to feel a connection, to unravel from the hurt and the habits that can ensue when ancestral wounding gets stuck in the body and the psyche.

When I travelled to Uganda in 2014, I had a very tough and tender conversation with my dad because I wanted to know where to go, where he used to race his motorbikes, the jungles he used to go camping in, the people and communities he was connected with.

His mother died in 1960, when he was 10. Her grave is one place he described to me before I left, and which by some miracle and perhaps fate, given the scant details and time that I had to find it, I was able to locate. He keeps by his bedside the frame of pressed flowers that I brought back from the tree that hangs above her fading headstone.

This year was the first time he voluntarily mentioned and spoke about the pain of losing his mother, and one of maybe only two times that I have seen him cry. The first was when I told him I was going to get married, the first time that I mistakenly did, hurting his heart in ways that I now realise was because he knew that he couldn’t stop me making a choice he could see I wasn’t reconciled with and which he knew (from his own parallel experience) would lead me to more pain than happiness. And true to form, he has always said I had no reason to feel guilty, that forgiveness (when I've apologised is required) isn't even relevant.

“You made your choices, you had reason to do so, and you stood by them, that’s all that matters. I’ve always been proud of you.” He told me, when that episode came up this Christmas, after he swiftly and characteristically moved on from recalling his mother’s passing.

He reminisced emotionally about the friends he made in England, the people who stood by his side, stood up for him, stood their ground, when he was turned down from work and faced racism in the small (minded) town he had to set up home for us.

The point is that my father told his own story, not one of struggle or endurance, but joy and freedom, youthful determination, of friendships and adventures.

As Ingrid Rojas Conteras writes in her essay ‘On Trauma’, featured in the book, ‘Letters to a Writer of Colour’, regarding her own process of “navigating the ramifications of ruin” in telling her story of leaving Colombia:

“The same material can feel gratuitous and exploitative, after all, or human and powerful, depending on who’s narrating it and how, and this is craft, and this is lived experience. It’s all in the telling.”

Over the course of one memorable day this December, my father did exactly that, reclaimed and breathed life back into his story, in his own words. He said possibly more than I think I’ve ever heard him say, about his own life, the choices he made, had to make, the people who meant so much to him and the memories of all the ones who were there for him in his hardest times.

"To learn to be a warrior is to learn to be genuine in every moment of your life." Chogyam Trungpa

With incredible detail and unprecedented exuberance he recalled one particular journey that he took by road in the late 1970s from England to Pakistan, travelling through Iran, Turkey and Afghanistan, determinedly and by his own admission stubbornly, disregarding and overcoming the obstacles of going through every border as a Muslim man with his family (apart from me; as a baby I was left with my maternal grandmother in England).

He recalled with relish and some surprise his boldness in forging his way onwards – partly reacting out of pride and indignation to a jibe from someone who had said he would never make the journey. He also recalled, and I have memories of this too, how I didn’t recognise and was scared of him when he returned with a face full of a new beard.

I’ve never seen him smile or laugh so much, as he reflected with reverence, gratitude, and a deep and broad perspective that proves what I’ve always known through our mutual wordless interactions and from what he has shown me – that it matters to keep going while we can, to take responsibility for our choices, to embrace opportunity, to stand by our decisions, to live with enthusiasm, and to relate to everyone we meet with an openness of spirit.

At the time of my own aforesaid marriage, where I didn’t abide my family’s wishes, once my dad reconciled himself with my decision and regardless, offered me the unconditional love he always has, I remember him telling me: “It doesn’t matter what anyone else thinks.” He stood by me, stood up for me, in the face of spoken and barely concealed contempt from some in the so-called community, where so much is about keeping up appearances, people pleasing and appeasing, about doing the “right” thing where right is actually wrong because it’s based on the idea of validation and approval.

Death came up as we talked. Death is always there, here. It’s cast a long shadow over our family’s lives, it’s taken many people away, including his beloved older brother and best friend Nazir. Recalling the time that Nazir caught up with him at the Equator line, as my dad was travelling back from what he thought was a secret visit to the woman he once loved and forsook to obey the family and marry my mother instead, my dad smiled through – for once – un-repressed tears, laughing, saying: “I don’t know how he knew, he always knew.”

It's a rare, wonderful and heart-swelling privilege to know my father a little more, to hear him tell his own story. And by extension, to be filled with gladness for who and how I am.

“Each of us will die,” he says, lamenting with deep compassion, and a little frustration, the nature of some of those we know who cling and continue to relive by retelling the pain their lives while disregarding the rest. “We never know if we will wake up in the morning. It doesn’t do any good to wallow. We have to get on with our lives and enjoy them.”

This is his story, and there is so much more to it. I hope in time to get to know more, and in that knowing, to live this life more freely.

Member discussion