Migration and the quest for freedom

How much does the past matter? How many questions do any of us have the right to ask of those for whom it was painful on a scale that we cannot imagine, let alone expect them to relive in the process of retelling?

These are questions I’ve contended with as the daughter of people who were forced to leave their lives behind due to the long, inhumane and destructive chain of cause and consequence of colonialism.

This history, their story, was a major factor in determining my desire to be a writer, and to focus on human stories and human rights and wrongs in particular. I spent many years working with immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers, alongside other professionals including lawyers and psychotherapists, supporting people who were robbed of their agency to find the degree to which it helped to remember, so as for the truth to be told and their rights to be recognised.

I believe in the vital power of bearing witness, of documentation, of telling stories. Equally, I’m aware of the importance of a more nuanced and sensitive understanding, of the potential for secondary traumatisation, of the not so clear-cut balance that has to be struck in terms of preserving and respecting people’s dignity while challenging the half-truths and blatant misinformation of public discourse and popular history as we currently (don’t fully) know it.

In 2014, as part of a lifelong conflicted quest to first know my own history and understand my family better, and secondly, to contribute to writing the real history of the Ugandan-Asian Diaspora, I travelled to the old haunts of my parents’ past lives. I’ve written a lot about all of that. I’ve also stopped (and restarted and stopped) writing about it. Because it’s complicated.

Writing about the past, one’s own and other people’s, is murky for so many reasons – the pain of recall, of asking, of vulnerability, exposure, the confrontation with realities and experiences it hurts and harms more to relay than to keep secret, unearthing memories that end up being tarnished by the present reality and forced recollection, the list goes on.

Nonetheless, this year marks the 50th anniversary of when my parents, among thousands of others, fled Uganda in fear for their lives and in uncertain pursuit of life the UK. I still believe in remembering, in opening our hearts and our minds to the lives of others, so as to know, to feel and to connect with the level of compassion and a depth of understanding that our common humanity merits.

So here is a piece from a series documenting the lives of my parents, and my attempt to honour their truth and the real story of a past that continues to have ripple effects.

“Every man has to learn the points of compass again as often as he awakes, whether from sleep or any abstraction. Not till we are lost, in other words, not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations." Henry David Thoreau, Walden

The road that stretches between Masaka and Entebbe is precisely 82 miles long.

82 miles of plastic carrier bags growing from beneath the cracks in the baking asphalt, their colours faded to nothing, disintegrated to translucent strings that swirl in the draft of each passing vehicle.

The noisy rush of drivers and the loads they carry is amplified by the exhaust fumes that fill the air with restless clouds of toxic smoke. Each car, each bike, each truck hammers away at the clay red dust kicked up by the potholed highway, deconstructed by time, remnants dissipated to nanoscopic particles of the past.

In the mirage created by the heat, everything seems to move in a slow motion haze, past the street sellers wilting in the shadow of the sun, the stalls of fruit ripening and rotting in quick succession in the oppressive heat.

The sweet and the sickly, the beauty and the dirt all intermingle and blend into one hypnotising experience. So all-consuming are the surroundings that it is as though you have been plunged into the edgeless canvas of a landscape painting where every object, every person, has been smudged into a disorientating existence.

Sat at the back of a crowded bus, I contend with an intense nausea caused by the lack of air-con and my position inches above the three foot tyres that are kicking up a haze over my sandaled feet, which sit throbbing by my rucksack.

I wonder how much of that road has changed since my father was here, counting each familiar mile. From Masaka to Kampala’s outdoor cinema to watch ‘Diamonds are Forever’ with his older brother. To Nakivubo Stadium to race his C2360 Czech motorbike, surreptitiously taken from his father’s car dealership in one of his many escapades out of the family’s overprotective clutches. To Entebbe airport, prematurely saying goodbye to his beloved dog Tiger, to leave the country for good.

The road once travelled

It’s 2014, and I too am on my way from Kampala to Masaka, 41 years since my father was forced to walk away from all that he knew and loved. To cross the Equator line as he did, to attempt to see what he saw, feel what he felt.

I have a vague idea of what I’m looking for, pieced together from the stories I’ve heard, faded family portraits, and the answers I managed to elicit from my parents as I prepared for this trip.

I’ve spent most of my life imagining how this expedition might pan out. Nothing could prepare me for the overwhelming sense of strangeness of the place that I am desperate to reconcile with the images I have conjured in my mind from the few things I know.

I’ve always been fascinated by my family’s origins, partly out of natural childhood curiosity, and partly because I wanted to be more confident than I was defensive when forced to answer that most invidious of questions, “where do you come from?”. Whether it was a question put to me in the faceless terms of the myopic ethnicity questionnaire, or the playground or pub variation of “no but where do you really come from?”.

Here I am, trying to find out. I feel a sickening sense of responsibility grip my stomach. Somewhat selfishly, I have always wanted my own voyage of discovery. Am I about to trample over something sacred?

My father has told me about this stretch of road many times. The exact distance is one of the few details of which he can be certain. Much has changed in the years since he went up and down that road, but the precise distance remains the same. Nothing can change that, not time, not people, not circumstance.

Sat across the dining table from my father six months before, in a corner of the East Midlands, 6,000 miles away from that bus, I started the conversation that I desperately hoped would lead me somewhere useful, for him, for me. To get a glimpse of the past in a way that might make real the places and the things that separate his former life from the one he ended up living.

Our facing chairs were like the ends of a bridge that day, which in spite of my emotional vertigo, I knew I had to cross.

The haze of the morning sky had burnt off as it turned nine o’clock in the morning.

My father had opened the curtains hours ago, to let in the early light, when everyone else was sleeping, padding quietly down the stairs with its fading opal blue carpet. He has always cherished the mornings. The solitude, the peace, the calm.

We can be miles apart and yet every morning, rising as early as he does in one of the many habits I have come to emulate, I’ll know that he is stood there in his pyjamas and dressing gown, by the open back doorway of the house I grew up in, starting his day before the birds have uttered a single sound.

Drawing on the first cigarette of the day, he’ll inhale deeper than his wheezing chest tells him he should, smoke trails drifting into the air, the familiar smell of Benson and Hedges, the same cigarettes he has smoked since he was 13, when his old scout leader offered them out during a camping trip to Lake Nabugabo.

It’s a smell I’ve come to love and hate for the simple reason that it is him and it is gradually taking him away from me.

Just as he crushed the cigarette butt into the ashtray, the ends cindering beneath the dry skin of his thumb, cracked deep from years of 14-hour days as a mechanical engineer, I made my way into the kitchen.

He had agreed to this conversation, I had to keep reminding myself of that. Still my face burned red with guilt, the as yet unspoken words constricted my throat from the fear of asking him about a life that used to be elsewhere.

A corner of England, 2013

What did this really have to do with me? What right do any of us have to intrude on another person’s history?

Conversations with my father are precious for their rarity. The comforting, rumbling baritones of his voice, the measured tempo with which he’ll say only what needs to be said. He is as precise with his words as he is at the art of maintaining a car engine.

He will talk when there is something to say. He will impart wisdom, advice, care and support. All the things that a father should. He is full of quiet grace. I don’t like to break his silence when there is no need because I see a gulf within him, a troubled place where it isn’t my business to go but where I nonetheless feel all the answers lie.

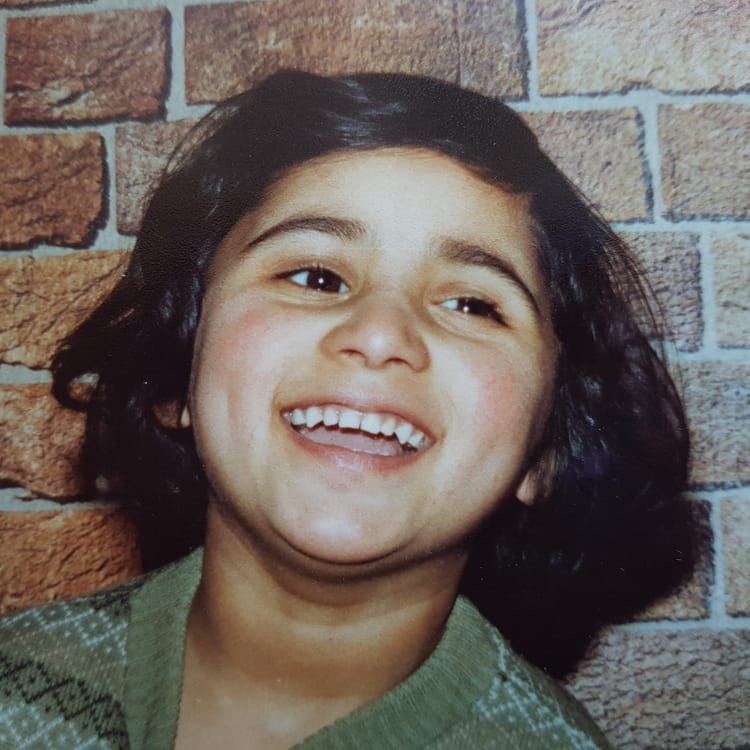

Leaning on the shelves, in the glass cabinet behind us, sit two children with their parents in the 1970s, in black and white. The youngest one, aged four, is me, trying to tuck myself in behind my father’s crossed legs as he looks towards someone else, a cigarette characteristically dangling from his index and middle finger.

My sister, aged eight, stands proudly, smiling for the camera, as directed by our mother, because it matters what other people think of you. It matters what people see, how they see you, what you are seen doing.

These images sit among ornaments and symbols of prayer. Relics and memories. Side by side. Testament to lost moments and the things we try to hold on to, the things that forever exert an influence, some more than others.

Sitting opposite my father at the table, I feel as though I diminish in size and become the child I was in that photo, blissful in my ignorance. There’s a part of me that would prefer to hide as I did then, to not be tangled up in this desire to know more while also knowing how hard it is to ask for the answers. I’d like my father to be comfortingly distracted by something more important than me, off scene.

Only he isn’t. He is giving me his full attention. This is painful, I think, and I haven’t even asked him anything yet.

I want to know him, to understand him, to bridge the divide. I also fear what will happen if I open up the uncomfortable silences that we have always respected in each other. What if he asked me such deep and personal questions? It’s testament to the man that he is that he allows me to break the silence of the morning and ask him to open up the wounds of the past.

He has only one clear window out and onto the world, his one real eye. The other eye still commands attention, but it moves a little less, follows only in motion rather than sight.

The story of how he lost that eye has many permutations. There are stories about the stories, doubts about what is real, suspicions about who was really responsible. He’s always protecting someone.

His face is at once changed and unchanged compared to the one behind him in the cabinet. I can see the difference there. He isn’t facing it. He can’t see it. I wonder if he ever looks, ever thinks about the times before, ever wonders “what if” in those quiet moments when there is no-one and nothing to interfere.

I know what has happened in the years between then and now. It’s the years before I want to know about, so I can piece together what has happened since.

“What do you want to know?” he says.

“Can you tell me what you remember?” as I release the words, I feel like an imposter on his private life. “I’d like to know where I should go, so that I can find the places you used to be. What was the house like where you used to live, do you think I’ll be able to find it?”

I may as well be five, asking these questions shyly, not the 36 year old that I am.

He sighs, his forearms extended along the table, his hands fiddling with a stray piece of paper.

“That was all such a long time ago now,” he says, not looking me in the eye. “Everything has changed so much.”

“Don’t you ever think about it?”

“There isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t think about it. ” he says, still keeping his gaze lowered towards the piece of paper that he has now folded neatly into the most compact of miniature three-dimensional squares.

“I think about what life would have been like, if we had hadn’t to leave.”

Uganda, 5 August 1972

Ahsan is riding down the road at 60 miles an hour, on his borrowed C2360 motorbike. His father doesn’t know that he’s taken the bike from the showroom back in Masaka, but Ahsan feels sure he wouldn’t mind, he’s only taking it into Kampala, he’ll be back before his father has time to notice. Besides, his father has never refused him one of the models from the showroom before, Ahsan feels certain he won’t mind, though best not to worry him by asking.

The pleasing roar of the engine fills Ahsan’s ears, drowning out all the peripheral noise of the side streets that he has become so familiar with. Eventually, he can feel nothing else, not even his fingers gripping the handlebars.

He is gliding through the air, his white open necked shirt billowing in the breeze, his loose cotton black trousers ballooning up, making him feel as though he is suspended mid-air in motion.

He tears along the 82-mile highway and arrives in Entebbe town, slowing down to pass the hawkers and the bus station, towards the crowds in the seats of Nakivubo Stadium. He feels his heart racing with the adrenalin of rebellion and the thrill of being in control of the engine he is sure will secure his victory today.

This is his one last rush of absolute freedom before him and his new wife, one month pregnant with their first child, will leave for Belgium. Soon there will be no more camping trips to the shores of Lake Victoria to watch the blue swallows return, no more idling around the jungles of Uganda with his hunting companions.

Shortly, he will meet the man who will alter the course of his fate in ways nobody quite yet realises. The man who takes direction from his own heavy and confused dream of mankind’s destiny.

This isn’t how Ahsan’s story is meant to go, but it will, because he isn’t in control of it.

Of course, there are some people who are aware of what’s to come. Paralysed by imminence, driven by self-centredness, they don’t tell anyone. There won’t be a single person left who doesn’t suffer as a result.

Not yet though, not yet.

Ahsan turns the bike into the stadium packed with people and the collective hum of suppressed tension and impatience. He eases off the throttle, lining up alongside the other men who have gathered on a football pitch for the rare occasion that it has been converted to a temporary drag racing track.

This is it. He thinks. He is ready. He smiles.

The man at the centre of the crowd stands waiting, waiting to crown a nation of winners. Waiting to laugh at the losers, all 70,000 of them. Waiting for his dream to come true.

This is it. He thinks. He smiles wider.

It is ten laps around the stadium. Ahsan is biding his time. He knows that to throttle the engine straight off will cause the engine to flood. That is the way to lose a race and kill the bike. He has no intention of doing either.

Taking it slowly, he tracks the speedometer, feels how the engine is powering up, listens with his fingers that detect the continual beat of the bike rumbling towards the perfect consistent pitch that tells him everything is as it should be. By the fourth lap, the grooves in the track are causing the bikes to skid and veer into each other. He though, has control.

His heart is calm, his mind is clear and focused. This is what he was made for.

He keeps it in the middle. Until the final lap. Then he carves his way through the struggling crowd of amateurs who have never handled an engine he way he has, felt its heartbeat, picked apart its innards and put them back together again in better shape than when they came into being.

He has it, he was always going get it. Winning was purely a matter of controlled force, action and consequence.

His hair caked back with the dirt and the sweat of the 38 degree heat, Ahsan pulls on his cigarette as he stands with the others, watching the smoke and the dust mingle in the air as the crowds grow impatient to leave now that the race is over. They are distracted by the commotion of the market outside of the stadium, eager to go barter for groceries they need and imported trash that they don’t.

Ahsan flicks his cigarette butt to the ground, watches the embers resist their ending, and makes sure the bike is firmly on its stand before he makes his way to the podium.

Idi Amin Dada, President of Uganda, dressed in customary khaki military garb complete with his soldier’s hat, shakes the hand of each of the riders. He is distracted, he is barely there, trembling with the excitement for the climax he has been waiting for.

Ahsan leans over the trophies to shake Amin’s hand as he must, this big, sweaty hand of misplaced power. With both hands, Amin grips Ahsan’s hands, shakes with one, passes him the trophy with other, and glares.

The red veins that branch from his shiny pupils, circled by pools of yellow, are darkening. Ahsan doesn’t even get the chance to look at his trophy. His hands are released and his fate is sealed.

It is a moment that has been some years in the making. A moment that has its origins precisely ten years before this scene when Amin took control of the country, where now there is what he feels to be a displeasing combination of ethnicities, a contaminating blot on his landscape.

Now here he is, presiding over a football stadium full of people half of whom he would soon be unpicking, the leeches he intends to remove from the over-milked cow.

“The Asians must leave,” he announces, puffing up his chest, turning away from the racers and facing the microphones that surround him and which he has become an expert at using. “Asians came to build the railway. The railway is finished. They must leave now.”

There are no photographs of that moment, only a few seconds of silent, grainy video footage, showing headless figures moving forward to a table lined with trophies, lorded over by Amin, shaking the hands of the racing drivers.

My dad is amongst them, though it’s hard to tell which one he is.

I have searched for evidence all these years, looking for some scrap of detail that will connect the then with now.

That moment that my father raced to short lived glory exists mostly as a memory, signified by the tarnished trophy that used to sit in the corner of our living room in the 1970s semi-detached house in the East Midlands that my parents have called home ever since.

It’s one of few items they were able to leave with. Other than a few photograph albums and a pair of wooden statues of African drummers, little else remains other than what they keep inside, buried deep, safeguarded from interfering with their resolve to get on with the lives they salvaged and rebuilt.

It’s why I’m in Uganda, looking for something to fill in the gaps, looking for my dad.

Member discussion